Simplify provider-payer collaboration for risk and quality gap closure

Arcadia Assess streamlines risk and quality gap closure for payer and provider collaboration — download the product info.

Traditional healthcare providers and payers have inefficient processes

Health plans and providers have traditionally relied on paper-based workflows to collaborate on risk adjustment and quality programs. Health plan quality and risk teams spend considerable time “chart chasing:” capturing evidence, calculating quality measures, and auditing charts. Providers often respond to multiple — and redundant — requests from health plans to capture and verify risk and quality data. These inefficient processes can result in subpar performance and a strained relationship between both parties.

Create effective provider-payer processes with cloud-based workflows

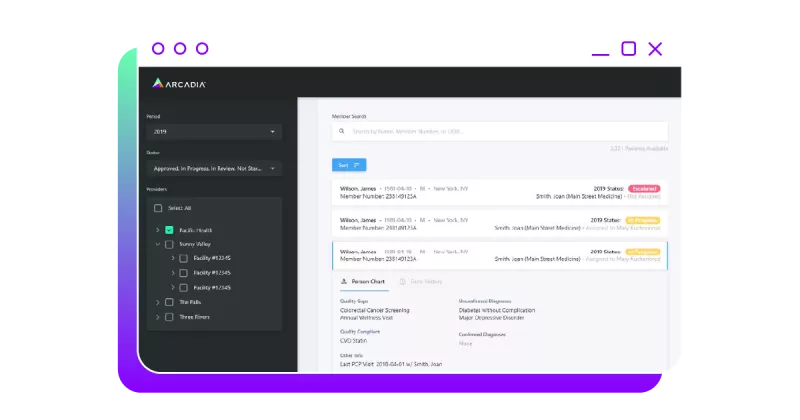

Arcadia Assess streamlines payer and provider collaboration that improves risk and quality gap closure through centralized, highly configurable workflow tools.

Seamless application. Elegant workflow and reporting structure.

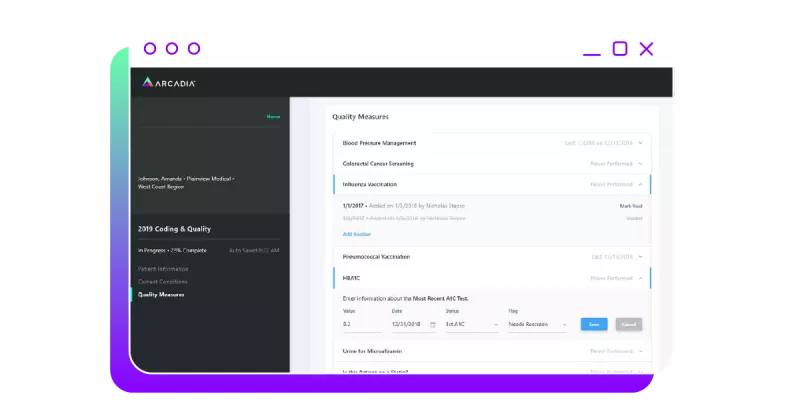

Quality and risk adjustment programs are available in a seamless application that gives providers an elegant workflow and reporting structure. Our tool is cloud-based and integrated, with claims feeds and clinical data, to facilitate combined risk adjustment and quality workflows for providers. These forms are dynamic and can be customized and triggered by health plan quality and risk teams.

Increase closure of risk and quality gaps

Track provider and program performance in near real-time

Reduce the administrative burden of chart chasing

Highly configurable views create workflows specific to your team

When your team is enabled with tailored workflows, they’re able to complete their work faster and more efficiently. Arcadia Assess workflows are:

- Highly configurable — Built to accommodate real-world variation between payers, health systems, and state requirements

- Customizable, dynamic forms — Augment risk and quality workflows with fully configurable form content for HRAs and other data capture

- Automated assignments — Create assignments automatically for providers and other users based on the type of gaps and eligible contracts

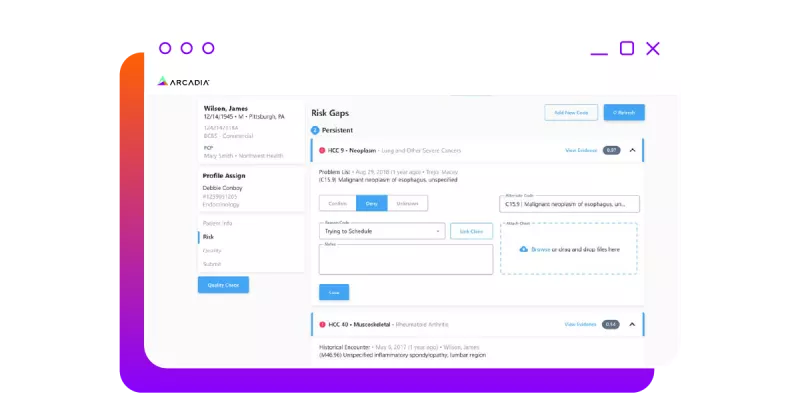

Simplify the process with near real-time provider-payer collaboration

Providers and payers are able to collaborate in near real-time as the system updates. This results in:

- Timely, clinical data — Integration with daily clinical data and claims feeds for timely view of risk and quality gap status

- Combined risk and quality workflows — Single application and programming engine for unified approach to quality gap closure and risk adjustment

- Integrated care management programs — Triggers interventions based on quality and diagnostic findings, and a shared record with care coordination staff

Payer-Provider Collaboration: Using shared decision-making as an outreach strategy to increase patient engagement

Beth Israel Lahey Health and Blue Cross Blue Shield Massachusetts recently implemented shared decision-making (SDM) to improve patient engagement in service of healthier lives.

Provider-payer collaboration streamlines success

Get a demo of Arcadia Assess and see how easy it can be for providers and payers to work together.