Population health trends across the United States

Ailing in Alabama? Hearty in Hawaii? A look at how states vary in their rates of common diseases, and why measuring health state-by-state requires robust data

When your days are full of healthcare data feeds from all over the country, you’ve got a unique window into larger national trends. That proves true for Arcadia’s Customer Insights team, who spend the hours between 9 and 5 (and, let’s be honest, sometimes a good deal later) combing through data points to discover meaningful insights.

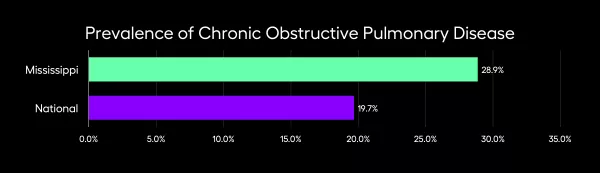

Recently, Dan Sweany, Senior Manager of Customer Insights, worked with his team to look at the prevalence of common diseases in a state-by-state breakdown. Studying each territory’s MSSP population (as of 2021), they looked at rates of diabetes, congestive heart failure, and dementia in most of the 50 states (there was a noteworthy exclusion, which you can read about below). Read on to learn what trends they discovered, the outliers that came as a surprise, and what healthcare experts can do in the future to further preventive care.

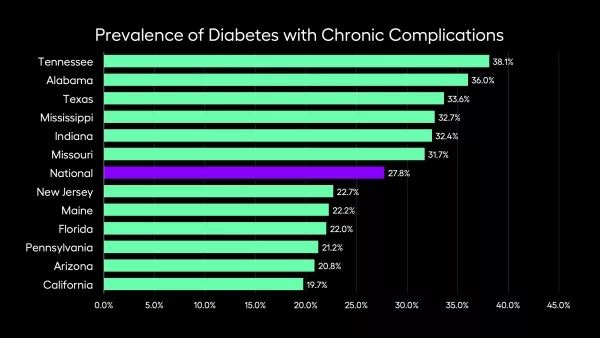

The states where diabetes dominates

The national prevalence of diabetes with chronic complications for MSSP patients averages 27.8%. When you travel the United States, that number varies wildly.

California, at 19.7%, sets the high bar with the lowest proportion of patients. On the other end, Tennessee has a staggering 38.1%.

“States that far exceed this average are primarily in the deep South, while those with rates far below average are primarily in the Northeast or the West Coast,” Sweany says. “Indiana is a high-prevalence outlier, while Florida is a low-prevalence outlier, regionally.”

The South has negative leaders for several conditions, so Florida’s place towards the top of this list is puzzling. Certain questions follow statistics that cover such a large range: what’s different about Florida than, say, Alabama right next door, with 36%? Is it a difference in demographics (a better gene pool? An influx of healthy new residents?), or is it a difference in quality of healthcare and screening?

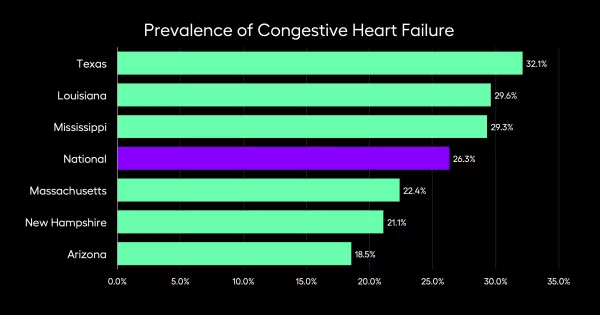

Where is congestive heart failure most common?

Rates of congestive heart failures prove similarly variable. With a national average of 26.3%, it’s bookended by Arizona (at 18.5%) and Texas (at 32.1%).

The South wasn’t a surprise, here, based on public health data that’s come out of the region, but Arizona was a less predictable frontrunner.

Like diabetes, there are certain questions that can’t be answered by this data alone. Are Arizonans taking long, brisk hikes over Camelback Mountain? Are Texans’ diets too high in cholesterol? For fellow frontrunners Massachusetts and New Hampshire, does adoption of value-based care mean prevention is more effective?

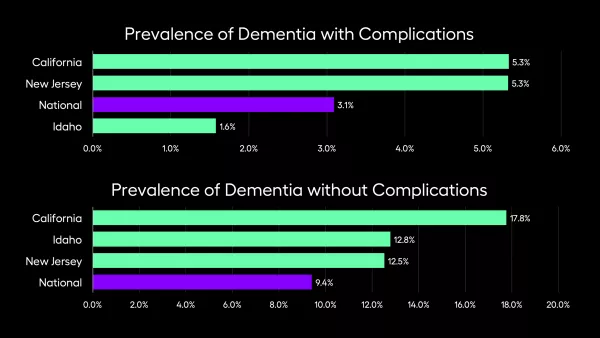

Dementia and how it varies state-by-state

The Customer Insights team broke these figures down into two separate disease categories: dementia with complications, or dementia without.

California and New Jersey have higher than average rates of dementia when compared to the national averages, both with and without complications. But Idaho’s prevalence is higher for dementia without complications, and lower with complications.

This could mean there are more people in California with dementia relative to the general population, but more likely, it has to do with reporting. California could be excellent at detecting and coding this condition, with incentives through programs like Medi-Cal or state reporting.

It’s an important consideration, and a necessary caveat before any true conclusions are made. While similar questions come up (like diet, lifestyle, or environmental factors), it’s also worth noting that these states are often dense, so people might be able to access routine care differently than they would in, say, Wyoming.

Data gaps, sample sizes, and other hurdles

Some of the most interesting, revelatory discoveries in this data pull happened when the Customer Insights team hit a stumbling block. Before settling on the three diseases featured here, Sweany and co. took a larger survey of what diseases occurred frequently in each state.

It was immediately clear, for example, that West Virginia had high incidence of lung cancer relative to other locales, but that realization was quickly followed by another one — the sample size of West Virginians wasn’t large enough to prove this statistically significant and rule out confirmation bias.

Sample sizes matter, especially for an outlier. Without a large group to study, there’s a risk of jumping to false conclusions (and knowingly or unknowingly affirming your own preconceived notions).

The unique case of Utah

The Customer Insights team couldn’t delve into every state, as they discovered when they looked at Utah. The numbers from that area were initially confounding — why were residents of that state so sick, in some ways, but also relatively healthy based on other metrics?

One culprit could be over-reporting.

“We’ve excluded Utah from every view here, because with the culture of that state and the demographics, they have very strong primary care relationships,” Sweany says. Utah introduces the complexity of socioeconomics when healthcare data’s on the line — people’s lives and identities affect their relationship to healthcare.

“There’s a higher prevalence because people are more willing to go to the doctor, and Utah’s got Castell out there, that’s very forward-thinking from a population health standpoint,” Sweany continues. “They’re very good at identifying and closing gaps, to the point that it looks like they have a higher-than-normal prevalence, because they’re working harder to close gaps.”

Though it wasn’t excluded from this study, California might be the same way. The state’s rates of certain diseases might appear high, but it could be because providers might be better at identifying issues (like early-stage dementia) and coding them. It makes sense, especially when the state’s adoption of value-based care and SDoH interventions are considered.

The intersection of hard data and human behavior

Knowing that Utah’s so successful in building relationships between primary care physicians and patients, the question follows — why can’t other states replicate that formula? It raises one of the most important takeaways from this data: no two states are exactly alike, demographically and socioeconomically.

“When you look at the socioeconomic factors in play, there’s not a large urban population in Utah, in general,” Sweany explains. “So some of the issues that impact a lower socio-economic population just don’t exist in Utah. We can say, ‘That would be great in an ideal state,’ but that’s saying that it’s possible to eliminate a whole chunk of a socioeconomic group from a population, when that’s not possible.”

Think about the way living conditions impact health. A state with a consolidated population of patients without cars might need to figure out a solution involving ride shares. A state facing an opioid crisis might put its resources there, even if their rates of diabetes or heart failure were also high.

There’s no one-size-fits-all solution, but there are some key takeaways.

“I think being proactive is something that all providers, in all states, should strive for,” Sweany concludes. What works in California may not be identical to the best programming in South Carolina, but a common thread in high-performing states is outreach and innovation, meeting patients where they are to mitigate problems before they start.

One nation, united by data

The first step in making meaningful progress is to know exactly where things stand. The Customer Insights team uses data to measure the current state of play, so Arcadia can partner with healthcare organizations to imagine healthier, happier days for all. Data lets you measure the distance between today and tomorrow, present and potential future.